Medoc Marathon

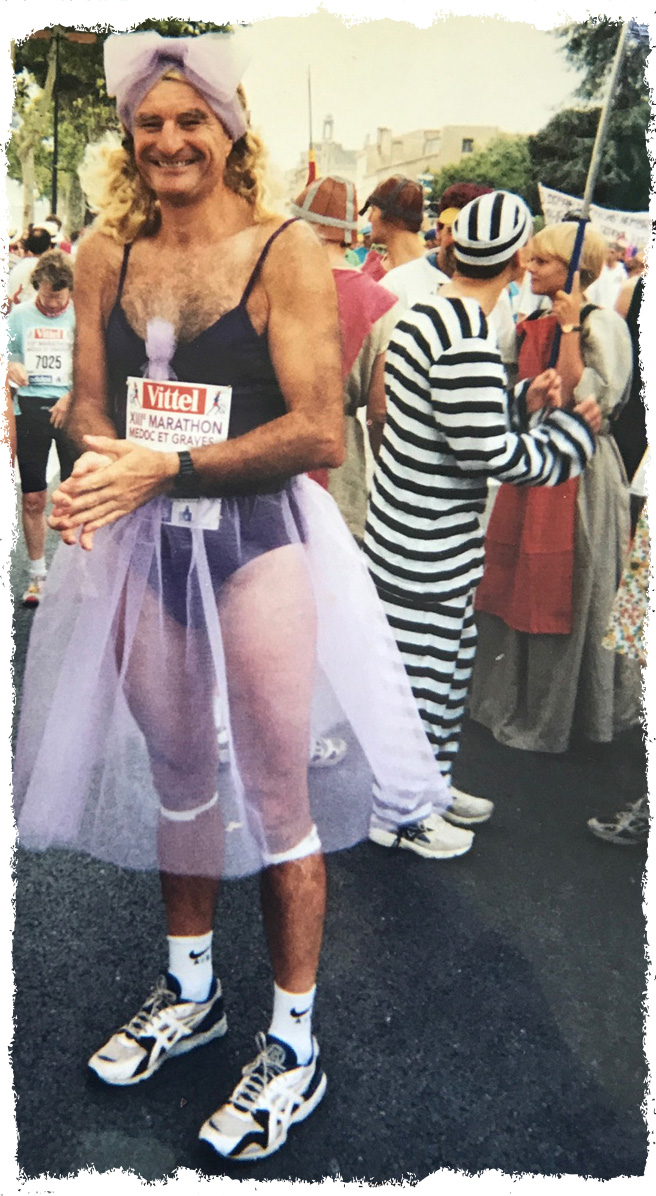

In 1997, I traveled to Bordeaux, France at the invitation of SOPEXA, the marketing board for French exports. To avoid being corralled into too many winery visits, I suggested that running the wine-soaked Medoc Marathon was more in keeping with my style of journalism. I documented the story for several publications including this version which appeared in Smoke, a thick glossy cigar magazine that disappeared with the last puff of smoke from the cigar craze of the 90s.

Years later while drinking scotch with my good friend Aynsley Vogel and blue-skying ideas for my next TV series, I used the marathon as an example of a quintessential episode. One scotch later we decided that the title of my article perfectly summed up the essence of the series. The name stuck, and in my first season I ran the marathon again—this time with a camera crew in tow. My mentor for that episode was Philippe Remond (aka Elvis), the marathon champion referred to in this story.

The first recorded marathon was run in ancient Greece by a courier forced to travel 26 miles to deliver an urgent message. After successfully reaching his destination and presenting his scroll, he keeled over and died. It is no surprise therefore, that since that time marathon running has been considered a sport for only the most disciplined and masochistic athletes. Except, of course, in France.

France, the land of epicurean delight, is the only place on earth where the idea of combining the intensity of a marathon with the pleasures of the palate is considered une bonne idee. Each September, seven thousand glowing runners from over twenty-two countries converge on the tiny town of Pauillac, population 5,855, in the heart of the fabled Bordeaux wine region. They gorge themselves on local delicacies, sample freely flowing Grand Cru wines, and run the requisite 26.2 miles— all at the same time. Think of it as a bad advertisement for the moderation movement.

France, the land of epicurean delight, is the only place on earth where the idea of combining the intensity of a marathon with the pleasures of the palate is considered une bonne idee. Each September, seven thousand glowing runners from over twenty-two countries converge on the tiny town of Pauillac, population 5,855, in the heart of the fabled Bordeaux wine region. They gorge themselves on local delicacies, sample freely flowing Grand Cru wines, and run the requisite 26.2 miles— all at the same time. Think of it as a bad advertisement for the moderation movement.

The Medoc marathon was conceived in 1983 after four doctors and a wine maker made a pilgrimage to the New York City Marathon. Though they were inspired by the raw energy by the event, they felt it lacked that certain je ne sais quoi. Convinced that pain could be coupled with pleasure, and experienced in a more festive and relaxed environment, they set out to design a serious marathon with a French sensibility. In their words, an event that took advantage of France’s cherished “natural resources”. By shifting the emphasis from the stopwatch to the stomach, and adding a generous

measure of joi de vivre, they created a unique event with a carnival-like atmosphere. As a testimony to their vision, Runner’s World magazine ranked it second only to the NYC marathon — quite the coup for a race that flies in the face of convention.

Pauillac is one of fifty-seven appellations that collectively make up the Bordeaux wine region. Driving along the narrow winding roads towards the village, one is immediatly struck by the beauty of the enormous chateaux that rise out of the rolling vineyards. In spite of styles that range from simple to wildly elaborate, they all seem steeped in rich wine-making history. It is somewhat surprising to discover that though some of the chateaux do date back to the sixteenth century, many are in fact modern replicas.

In the early 1970’s the bottom fell out of the Bordeaux wine business. Inflated prices caused by greedy speculators in the international marketplace caused futures to rise beyond what the market was willing to bear. Many family-owned wineries were left holding hundreds of thousands of bottles. In the following years, the upkeep of the Chateaux and vineyards fell prey to the dwindling demand. Then in mid eighties, the multinational insurance company AXA bought up four of the top properties, instantly transforming itself into one of the world’s most powerful wine conglomerates. They immediately installed a hand picked group of local vintners to manage the operations. Over the next decade they invested heavily, rebuilding cellars, putting the vineyards back in order, and refurbishing —and in many instances rebuilding — the historic chateaux from the ground up. The Medoc marathon’s path is a feast for the eyes, winding through the ornate gateways of these architectural wonders and along their ancient tree-lined lanes.

The evening before any conventional marathon, competitors usually eat a simply prepared bowl of pasta and retire early for a good night’s sleep. Not in Medoc. At the carbo-loading nuit de milles pates (a clever turn of phrase meaning both night of a thousand pastas and the night of a thousand feet), fifteen hundred runners feast on a sit-down, four course pasta dinner. Each place at the long family-style tables is set in the French tradition with an array of wine glasses, one for each of the local wines selected to accompany the respective dishes. After all, why should this night be different from any other? The prize for the most creative use of the nutritious noodle goes to the pastry chef who dreamed up creme brulee aux vermicelles (yes, that is creme brulee topped with vermichelli noodles). Following dinner, it’s more drinking and dancing to the beat of a eight piece blues band.

Nine hours later, the human energizer bunnies congregate along the Rue Le Quey, looking surprisingly effervescent after the previous night’s revelry. As if the prospect of running a marathon hungover isn’t challenging enough, more than half of the competitors up the ante by wearing costumes — some of which are so elaborate that it is hard to imagine how they even made it to the starting line. A quick survey reveals clowns to the left, jokers to the right, Vikings, bumblebees and Matadors, standing shoulder to shoulder alongside an amusing cross section of hairy, muscular-legged transvestites (a testament to the fact that French men will go to great lengths to dress up in woman’s garments). Somewhere around 9:30 (precision is not a hallmark of this race), a confetti-spewing cannon unleashes the bon vivants into the sleepy streets of Pauillac, past the patisseries, charcouteries and cafés. The first mile is more of a crawl than a run due in part to cobblestone streets that are barely wide enough to accommodate a few strolling tourists, never mind thousands of adrenaline filled runners. As it turns out, there is another reason for the slow start. A team of ten runners, pulling a fifteen foot high replica of a windmill on wheels, has run up against a Citroen-sponsored squad pushing the hollowed out chassis of a Deux Cheveaux, thereby causing a major bottleneck. The resulting traffic jam cost those trapped behind it several precious minutes. Instead of the profanities that normally spew forth at a time like this, the idling runners cheered the crews on with good natured chants and songs. Then, after a two mile loop through the village, the old ochre sandstone dwellings are left in the dust. Postcard vistas of wide open rolling countryside and never-ending rows of well groomed vines begin to reveal themselves at every twist in the road.

Nine hours later, the human energizer bunnies congregate along the Rue Le Quey, looking surprisingly effervescent after the previous night’s revelry. As if the prospect of running a marathon hungover isn’t challenging enough, more than half of the competitors up the ante by wearing costumes — some of which are so elaborate that it is hard to imagine how they even made it to the starting line. A quick survey reveals clowns to the left, jokers to the right, Vikings, bumblebees and Matadors, standing shoulder to shoulder alongside an amusing cross section of hairy, muscular-legged transvestites (a testament to the fact that French men will go to great lengths to dress up in woman’s garments). Somewhere around 9:30 (precision is not a hallmark of this race), a confetti-spewing cannon unleashes the bon vivants into the sleepy streets of Pauillac, past the patisseries, charcouteries and cafés. The first mile is more of a crawl than a run due in part to cobblestone streets that are barely wide enough to accommodate a few strolling tourists, never mind thousands of adrenaline filled runners. As it turns out, there is another reason for the slow start. A team of ten runners, pulling a fifteen foot high replica of a windmill on wheels, has run up against a Citroen-sponsored squad pushing the hollowed out chassis of a Deux Cheveaux, thereby causing a major bottleneck. The resulting traffic jam cost those trapped behind it several precious minutes. Instead of the profanities that normally spew forth at a time like this, the idling runners cheered the crews on with good natured chants and songs. Then, after a two mile loop through the village, the old ochre sandstone dwellings are left in the dust. Postcard vistas of wide open rolling countryside and never-ending rows of well groomed vines begin to reveal themselves at every twist in the road.

In the spirit of a lengthy French meal, runners savor the pleasures of the course instead of rushing through it. And there is plenty to savor. Starting at mile five, each of the twenty-three chateaux along the route proudly provide the runners with samples of their wines — in glass stemware, no less. Lafite, Mouton Rothschild, Latour and Lynch-Bages — the names read like the wine list of a Michelin three star restaurant. Even teetotalers would be hard pressed to pass up such offerings. At the first stop, the elegant Chateau Beychevelle, runners pause to reverently swill the elixir and compare notes. There is something undeniably absurd about a man in a little red riding hood costume and a pair of top-of-the-line Adidas, earnestly contemplating the bouquet of Chateau Beychevelle’s Grand vin 1994. Of course fine wine is not meant to be drunk alone. To complement it and provide much needed energy, a variety of gastronomic delights are dished up roadside by a gaggle of volunteers. Early on, fresh and dried fruits are served to tease the palate, before the menu changes to a smorgasbord of meats and cheeses. Even between refreshment stations, runners can replenish their energy levels without breaking stride by leaning down and scooping up bunches of plump crimson grapes, only days away from the harvest, and consequently brimming with sugar. Veterans of the race however, know to leave room for the gastronomic holy grail that awaits them further down the road. To speed their journey, more than fifty musical acts, including Basque gypsies, samba groups and leather clad rock bands — looking far worse for the wear in the early morning hours than the runners themselves — grind out a steady beat

One way or another, the race touches virtually everyone in the region. Over twenty-two hundred volunteers staff the event, including many of the town’s children who double as judges for the costume contest. The remaining townsfolk line the streets to cheer on the participants, or watch from blankets amidst their own elaborate picnics and bottles of vin de pays. The festive sense of warmth and community is contagious.

As the race progresses past the midway point, the teams of shackled prisoners and other festooned runners fall back in the pack as their costumes begin to take their toll. And the front-runners start to look more like the lean mean running machines one would expect to see at a marathon. In addition to providing much needed distraction, the masqueraders have also made a valuable, if highly unusual, contribution to the welfare of some of the runners. During a particularly nasty stretch of head winds, the very resourceful runners tucked themselves behind members of the potato team. Coasting in the back draft created by the oversized costumes, they were able to recoup some of the valuable time lost in the early traffic snarl.

As the race progresses past the midway point, the teams of shackled prisoners and other festooned runners fall back in the pack as their costumes begin to take their toll. And the front-runners start to look more like the lean mean running machines one would expect to see at a marathon. In addition to providing much needed distraction, the masqueraders have also made a valuable, if highly unusual, contribution to the welfare of some of the runners. During a particularly nasty stretch of head winds, the very resourceful runners tucked themselves behind members of the potato team. Coasting in the back draft created by the oversized costumes, they were able to recoup some of the valuable time lost in the early traffic snarl.

The twenty mile mark known to marathoners as “the wall” is the point at which most runners suffer a total depletion of their stamina and enter a state which is best described as runner’s dementia. To snap them back into the absurd reality of this race, the organizers have once again injected some comic relief by building a faux brick wall, constructed from Styrofoam. The runners literally have to break through the wall in order to continue the race. Crossing this physiological barrier helps them manifest the second wind required to face the last six grueling miles.

Along the home stretch, at mile twenty-four, is the race’s most celebrated pit stop. Runners approach a modest road-side cabana to find the holy grail of energy food. Mounds of locally harvested, freshly shucked Atlantic oysters glisten in the sun. They slide easily down the eager gullets of the galloping gourmets along with more wine, which by this point has acquired medicinal value as a painkiller.

With a menu degustation like this, it’s not surprising that prize money and luxury cars are not required to lure a field of athletes from around the globe. Granted, Medoc is not a mandatory stop for world-class runners, but it draws its fair share of the elite crowd, including France’s reigning marathon champion, Philippe Remond. For the forth year in a row, Remond, a dead ringer for a young Elvis, lead the pack as he approached the ceremonial red carpet leading to the finish line. With a fellow team mate team hot on his heals, he broke the ribbon in a respectable 2:27. In the ceremony that followed the race, Elvis and the female winner, Anne Dieltiens (2:55), collected the enviable prize — their respective weights in first growth Bordeaux wine.

During the next four hours, long after the winners have showered and changed, the remaining herd jubilantly sprint, walk, and sometimes crawl across the finish line. As in all marathons, there are no losers. Every finisher is greeted with a kiss on both cheeks, a commemorative medallion and, surprise. . . a bottle of Bordeaux.

The Medoc marathon has earned its nickname le marathon le plus long du monde (the world’s longest marathon). Aside from the literal interpretation applying to the last third of the field who clock in at over 5 hours — an oddity in competitive marathoning — it seems to go on forever. The day after the main event, the bravest of the brave rise to participate in a 10K walk that revisits some of the course’s highlights as well as some new sites. And wouldn’t you know, this walk too includes several wine tastings.

Despite the ludicrous quantities of consumables and the non-stop partying, the Medoc Marathon casts an undeniable spell. This writer’s experience is a testimony to it’s magic. I arrived in Medoc grievously under trained, a full decade after my last marathon, and suitably apprehensive about the challenge I had undertaken. Yet, in the interest of journalism, I felt compelled to sample the cornucopia of delights, regardless of the consequences. I still managed to clock in 3:44, knocking ten minutes off my previous time. Coincidence? I think not. As they say in France,Vive la difference.